The piece below was originally produced for a CST course for Headteachers accredited by the Archdiocese of Melbourne in April 2021

———-

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. I took over two schools – my first leadership position – 3 months before a pandemic swept across the world and we were forced into closing our doors to all but a small number. The optimism and energy of a first leadership post soon gave way to the daily toil of risk management, health and safety and safeguarding. These were times when we were called to authentic, selfless witness and, if I’m honest, I wasn’t ready for it.

Not that I didn’t say the right things, course. I had the phrases as much the theology and was sure these were my armour and shield in what was to come. Those early days seem so remote now – the things that occupied our minds and our energy back then seem so trivial today. I would say I had hope, but it was a superficial sort – the frivolous desires of a comfortable soul.

If hope is a supernatural virtue then its foe is very much of the earthly realm. We talk about inequality in our political discourse, but more than anything it is straightforward deprivation which starts to corrode optimism. It demoralises. It strips of dignity.

I forgot this. I used to know it, but I forgot it. And in so doing the service of our community was reduced down to one of material transfer, as if food on the table provides food for the soul. It helps, there is no doubt about that, but the number of families just about holding on right now suggests it is more necessary than sufficient.

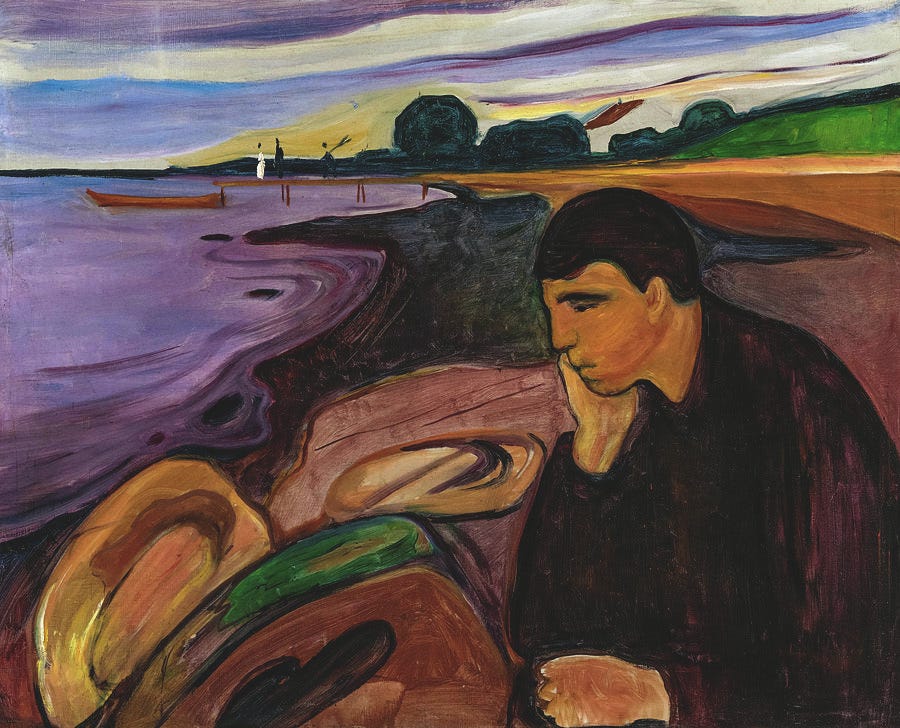

The most recent lockdown has been by far the worst. Most of our time is dealing with the broken – our children, our families, our staff, myself. By broken I don’t mean unable to function, unable to contribute – it is something more ghostly than that. Rather, it is a loss of spirit, a malaise, a quiet sigh and downward cast of the eyes. It is not the lack of a smile but the loss of joy; it is not the complaining but the forbearing. People are weary and are suffering. And with it, one sees the invisible threads that tie us one to another begin to fray. Despair no longer seems a theological category but the only description that quiet captures the mournful reality.

After leading two schools through one of the most difficult years in recent history, I have to tell you that most of the time it has felt hopeless. Strictly speaking, I mean that in the secular sense – the feeling that for all you can do, there is just so much you can’t, and for all you have done, there is so much you haven’t.

But then perhaps to be hopeful, you must first be humbled. Indeed, maybe you must even despair. Vain beliefs about my capacity to control and deliver was an obstacle to real hope – it is the disconcerting loss of both which compels me to thrown myself upon that Love. It is amazing how often the sincerity of prayer correlates with the sense of self-power – and how the loss of it can force one to confront precisely this pride. It feels a little uncomfortable to say this, since those we serve deserve better than to have their suffering glibly explained away as the opening for grace – we must avoid a sort of spiritual jam tomorrow which neglects the suffering of today.

But as time ticks on, you stand there, humbled, beaten, broken before the Lord, and no other words suffice except a quiet pleading, unspoken, from the depths, placing oneself at the mercy of Him who can scatter the proud and raise the lowly. As Christ promised:

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven

Blessed are the meek; for they shall inherit the earth.

Perhaps this is the real battle hymn of the humbled.

I think perhaps this promise is our best hope.

Leave a comment