The face plate opposite adorns the tomb of Philip Howard, who died in 1786 while in the service of the King of Sardinia. It is a moving tribute and speaks of the earnest desire of an Englishman to serve his country, even whilst precluded from doing so. His patriotism was clear; his cultural endowment ought to have been equally so.

The face plate opposite adorns the tomb of Philip Howard, who died in 1786 while in the service of the King of Sardinia. It is a moving tribute and speaks of the earnest desire of an Englishman to serve his country, even whilst precluded from doing so. His patriotism was clear; his cultural endowment ought to have been equally so.

But it wasn’t. The Howards were recusants, seeking to uphold the Old Faith against a political elite determined that such obstinacy was tantamount to sedition. And this little Anglican chapel nestled on the western banks of the River Eden at Wetheral, with its mausoleum hidden away through the north transept, housing the testimonies and remains of ‘papists’ and bearing this poignant plea for clemency, stands in quiet witness to the messiness and splintered loyalties bequeathed by the Reformation and the persecution that followed (the chapel was originally the local church for the Howard family of nearby Corby Castle, the same Howards who, following the emancipation of the Roman Catholic Relief Act in 1829, commissioned A.W.N. Pugin to build a Catholic church, further away though this time on their side of the river). Whilst another branch of the Howard line, based ten miles to the east at Naworth Castle, eventually conformed (with inducement to do so – Charles Howard was made first Earl of Carlisle), others held firm and became outcast.

And outcast really is the word, especially if our interest is cultural inheritance. Loyal Catholics, during that period described by Cobbett as ‘an alteration greatly for the worse’, had their wealth purloined as much as their stake in society, and found themselves asset-stripped as the Acts of Uniformity, the Test Acts, and myriad other laws achieved their principal objective and diminished the influence and position of Catholics. Cultural alienation followed – notwithstanding notable exceptions, from Byrd to Tallis, Campion to Shakespeare(!), it is difficult to generate, let alone bequeath, great art, literature and architecture, while isolated and stripped of the web of relationships and influence that underpins such flourishing. From patronage to possessions, Catholics found themselves outcasts in their own lands, a land they built, a land which bore the marks they laid upon it, which sang the testimony of their deeds in stone and quill.

Since exclusion was as much about ideas as it was property portfolios, so ignorance of, and hostility toward, the Catholic faith became a way of asserting rightmindedness and affirming social credentials – to be a member of the in-crowd, one had to be able to mock and ridicule Catholics, to repeat and defend what Newman called the ‘myths and fables’ of the anti-Catholic record. The temperament remains prevalent today, with ignorance of the Faith seemingly synonymous with a cultured worldview and an elevated intellect (one might point to the jingoistic whiggery of Michael Gove’s recent offering as a fine example of this enduring phenomenon). And politically, too: we fight for our right to exist in the state sector, and put at risk our employment within it where our adherence to doctrine might be deemed incompatible with the dictates of the state. How poetic history can be.

What relevance has any of this to curriculum? Well, it is important to state these truths, since this is the historical milieu from within which our educational canon is constructed, the well from which our intellectual waters are drawn. If we are to discuss what we deem worthy of transmission from generation to generation then the curation of that canon, and the judgement of what best comprises it, is a matter for scrutiny, lest we risk repeating the disinheritance and wrongly calling it scholarship.

For myself, this has become a more pressing matter in recent weeks, as we look at ways we can develop a core knowledge curriculum at our schools, a broad vision of learning which really does offer, to quote Arnold, the best of that which has been thought and said.

And here one runs into difficulty. Bluntly put, one is tempted to question whether the Hirschian approach, and more so the evangelism of his disciples, might be insufficient for the task. It seems increasingly the case that the core knowledge movement restricts itself to the straight jacket of secularity, cutting itself from whole fields of interpretative frameworks and placing insufficient stress on theology and especially Scripture. For many this presents no barrier (I have seen few protest the point), either lacking the personal belief to deem it important or working in a non-church school where it might be deemed inappropriate anyway. But surely this is to accept an impoverished canon, blind not only to the realities of our shared history but also to the very concept of core knowledge and cultural capital in the first place.

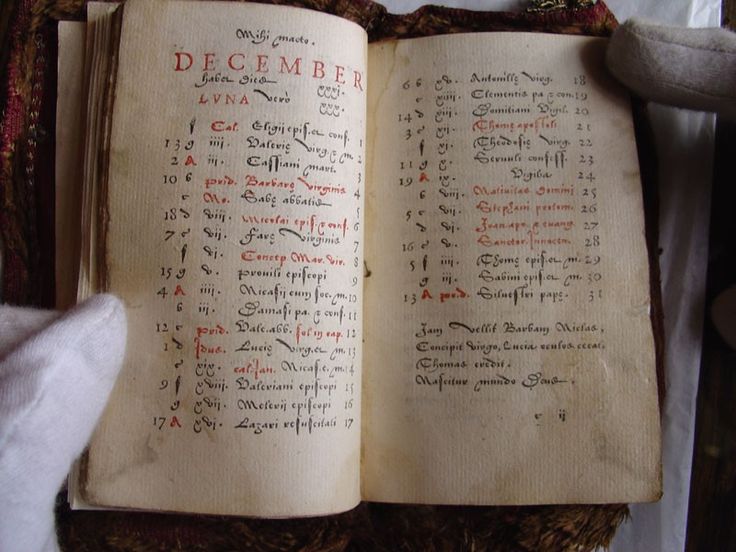

Examples? Well, prayer is an obvious place – is Kipling’s If self-evidently more worthy of recitation than the Our Father? Is the rosary in possession of less cultural capital, and worthy of less attention, than Shelley’s Ozymandias? Is the liturgical year, the cadences of which shaped the very psyche of our island and the customs and rituals therein, unworthy of detailed study? Is scripture, which lay at the heart of learning for hundreds of years and shaped everything from our laws to our literature, not a foundational aspect of any coherent concept of cultural capital? And lastly, is theology, the lens through which one must approach so many historical events to have any meaningful understanding of them, not worthy of as much attention as the events themselves?

In short, if one starts from a position of neglecting the religious and theological backdrop of the culture in which so much of our cultural inheritance was formed, what is offered is but a shadow of artefacts, and ultimately historical and cultural illiteracy, a secular humanist wish-projection of what our shared history and identity should have been, rather than what it practically and really is.

Which brings me back to our schools. Taking into account this deficiency, wanting to give a fuller account of that cultural fruits we wish to see preserved and bequeathed, do we, as a Catholic federation, need a Catholic canon? One hundred and sixty five years after Newman sought to define the proper curriculum of a Catholic university, must the Catholic community undertake a more systematic effort to define the proper curriculum of a Catholic school? Do we need to stake out our own vision, to include those treasures of our own that have not only been neglected, but from which we have been excluded? Something of the sort does exist, though not in a collated or systematic form. Should that be our next project? And if so, does that undermine the very notion of a canon, by definition shared and universal, or reaffirm it?

Or should we accept what we might believe to be a sanitised product, projecting an account of worthiness defined, ironically, by the whims of the now? This would certainly be easier. But I for one cannot shake the feeling that we might have something worthier still. Or put another way, would a Catholic canon cast aside the secular in the same way the secular casts aside the theological, or a thousand years after last having done so would it instead preserve them equally since, as with Chesterton, ‘it is only Christian men/Guard even heathen things’?

I’d certainly welcome your thoughts.

Read the follow-up post, including an email dialogue with Hirsch, by clicking here.

Leave a reply to Forming the Curriculum « Outside In Cancel reply